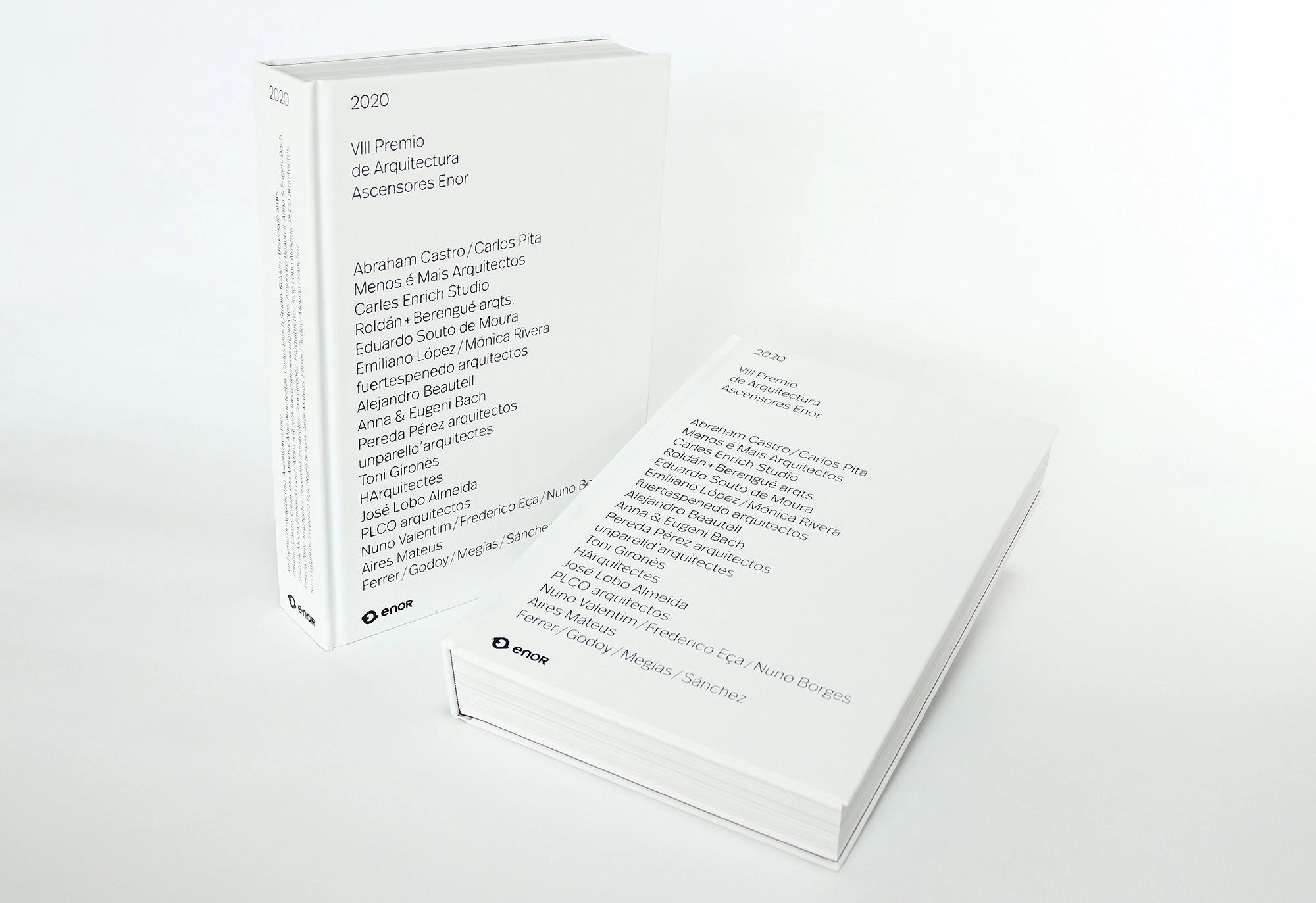

On the occasion of the presentation of his Grand Prize for Architecture, Enor presents the 480-page book-catalogue with all the projects of the winners and finalists. Since the first edition...

On the occasion of the International Conference on Construction, Energy, Environment and Sustainability (CEES 2025), held in Bari (Italy) in June 2025, rusticasa® had the honor of being featured in the presentation Market Readiness in Timber Construction: The Role of European Technical Assessments, delivered by Eng. Rui Jerónimo.

Casa do Rio is a finalist for AIT-Award 2020 | Best in Interior and Architecture, in the “Hotel” category. The result will be known on 11 March at the award ceremony in Frankfurt. In the...

Use of cookies

Our website uses cookies to improve the browsing experience and for statistical purposes. For more information, please consult our Cookie Policy