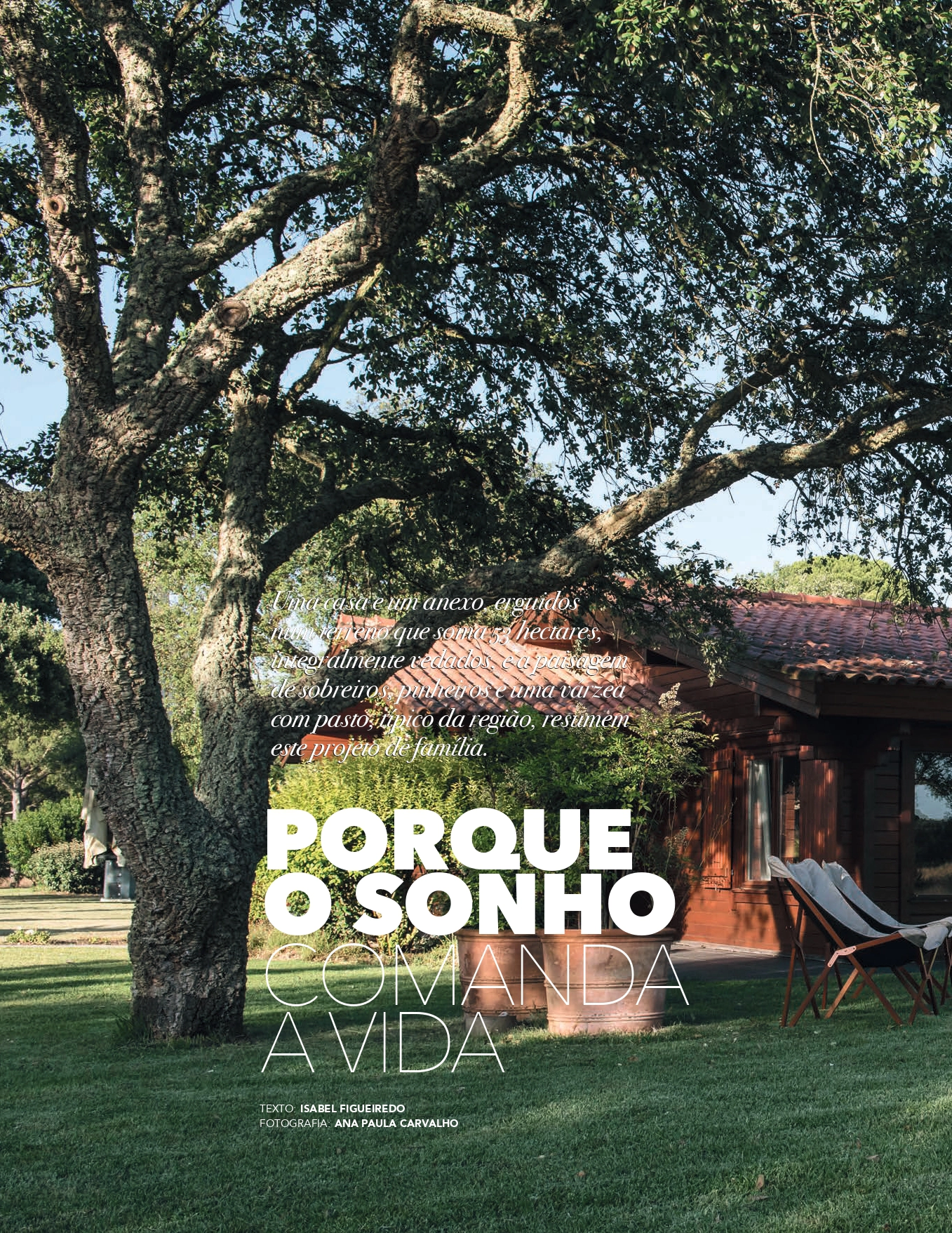

In issue nº 187 of the Casas de Portugal magazine, we find an extensive photo reportage of a rusticasa® built several decades ago. Set on an Alentejo estate, on the edge of a lake and...

Casa do Rio Rural Hotel, in Vila Nova de Foz Côa, won the 2019 National Award for Wooden Architecture. The architect Francisco Vieira de Campos’s project for Quinta do Vallado was...

rusticasa® introduces its new ITS™ (Insulated Timber System) building system with NATURLAM® self-supporting panels. The glued laminated wood panels insulated with cork at its core...

Use of cookies

Our website uses cookies to improve the browsing experience and for statistical purposes. For more information, please consult our Cookie Policy